A Bad Week for Saltley by Syd Williams

Whilst shed accidents involving locomotives occur from time to time they are comparitively rare and usually mean embarassment for the causers rather than serious or fatal injury. The usual result is often illustrated by a photograph of bystanders at the turntable pit bearing a " How do we get the loco out?" or " Who's going to tell the shed foreman?" expression.

The larger the shed the more engine movements and statistically the larger sheds should have more incidents but even so the numbers are generally low. There was, however, an extraordinary week at Saltley in the early fifties recounted by Terry Essery in his biography 'Firing Days at Saltley' and I am indebted to the publishers for giving permission to reproduce the story.

It all started when a Senior Driver nudged the shed wall with a Class 5 as he was moving the locomotive prior to leaving Number Three shed. He admitted to an error of judgement and apart from putting a bulge into the aforesaid shed wall, which was the one common to Number One and Number Three sheds, little damage was done.

However this for some reason set the scene for a jinx to reign over the Depot. Not to be left out of things a quota (disposal) man effectively punched a hole clean through the canal side wall of Number Three shed with an 8F and deposited about two tons of assorted masonry into a twelve ton open wagon which was conveniently parked on the track outside. At least this reduced the clearing up time. The following day some marshalling men got carried away and a dead engine which they were moving for the fitters managed to run off on its own and constructed a neat (and now new) third exit in Number One shed.

Getting into the spirit of competition, a Passed Cleaner who really had no business to be driving at the time, demolished, with the aid of an 8F another section of wall in Number Three shed, this time adjacent to the diesel oil storage tank. Meanwhile the men out in the shed yard, intolerant of being outdone by their colleagues inside, tore the side out of a Class 5 tender which was standing foul on one of the disposal pits. The day's destructioun was rounded off by a substantial head-on collision between a Black 5, which was being prepared for a Carlisle job and which had been backed under the hopper to top up with coal, and a 4P tank engine manned by an eager disposal crew who failed to realise that the Class 5 having coaled would be coming back up the arrival road. Extensive damage was caused to both engines.

The campaign to deplete Saltley's locomotive stud was re-established a day later when a Super D and a 3F, which were coupled together for the convenience of a disposal driver, ran away unmanned down to the stop block at the end of the ashpits. The combined weight clouted this formidable and ancient structure with sufficient violence cause extensive damage to both engines' buffer beams and frames.

The climax occurred at Friday lunchtime. One of the quota team was disposing a Compound 4-4-0 and, whilst waiting to enter Number Two shed, had filled the boiler to a greater degree than was strictly wise. This also had the effect of reducing the steam pressure to little over 100psi. The steam brake on a Compound is notoriously ineffective particularly when steam pressure is low. Perhaps the designers, in their wisdom, envisaged the engines being used only on trains with a continuous braking system. Another awkward thing about Compounds was that they often tended not to respond to an initial opening of the regulator and there is a considerable delay before the wheels start to rotate. Moreover, 24 turns of a very stiff reversing screw from full forward to full reverse gear (or vice versa) preclude any swift change in direction should the need arise to help out the lack of braking power. All these factors can add up to a very lethal combination when trying to operate in an emergency. Whatever the reason, the Compound was given a good handful of of regulator when it seemed reluctant to move off the turntable. Then it did move with a rush, with the 7 foot driving wheels slipping violently. All that momentum could not be arrested in the few yards available and the result was that the engine, still travelling at a fair speed, jumped the pit stops and crashed tender first with terrific force into the shed wall which divided it from the main office. So great was the impact that a section of wall roughly the size of the tender exploded into the office and some portions of thick brickwork flew right across the room and through the windows on the opposite side Only a few minutes earlier members of the office staff were working in this area and, had they not just retired for lunch, would cetainly not have lived to see another day. The damage took some time to repair, and being next to the enginemen's lobby no member of the footplate staff could fail to see the extent of the devastation or realise the possible consequences.

This must have had a sobering effect on the shed staff being shaken by the near miss and possible loss of life. They then took much more care as no incidents occurred for some time afterwards. The jinx had disappeared and things went back to normal. From then on the number of incidents were within the bounds of reason for a motive power depot the size of Saltley were reported.

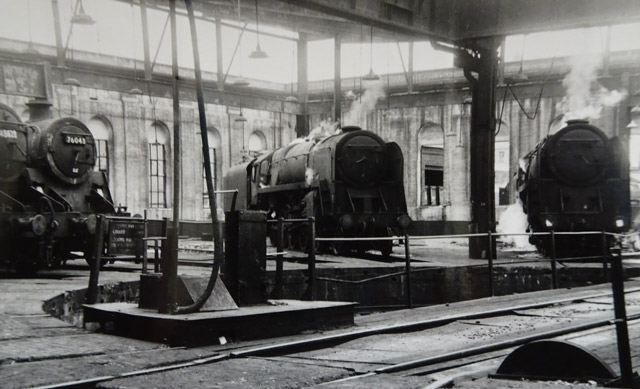

The interior of Saltley MPD in 1966. Photo - MLS

Collection.

Last update April 2018. Comments welcome: website@manlocosoc.co.uk